Intelligence or robotization? Where are we heading?

“The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt”– Bertrand Russell

“If you make people think they’re thinking, they’ll love you; But if you really make them think, they’ll hate you”– Don Marquis

“Mundus vult decipi, ergo decipiatur” – Petronius (People want to be fooled, so let’s fool them)

Everybody talks about intelligence: verbal, spatial, emotional, strategic, social—there are countless tests claiming to measure it. Yet we’re still far from having a clear definition, especially since it seems there are many types of intelligence, and we often confuse technical competence or culture with intelligence.

What’s more, ever since computers appeared, a whole series of activities once considered “intelligent” have been taken over by machines, making things increasingly confusing. For instance, just a few decades ago, anyone would have agreed that playing chess was a demonstration of intelligence. Now, however, a machine—applying a few algorithms—can defeat the world chess champion. The same goes for many other activities we naively believed no machine could ever do.

And yet, we feel that these machines and computers, despite their performance, are just dumb tools, devoid of awareness. We feel that intelligence is something else. I won’t get into the debate around defining intelligence—that would take us too far. Instead, I’ll turn to etymology, as I usually do when I want to truly understand a concept.

The word “intelligence” comes from Latin: inter ligere = “to read between the lines.” Since ligere/legere also means “to bind” (from the root leg, “to put together”), inter ligere also means “to make connections” (or “links”).

So intelligence is the ability to create connections between seemingly unrelated things, to go beyond the obvious, and “read between the lines” to discover the hidden truth behind them. Needless to say, the words “to understand” and “wise” carry the same significance.

I can’t think of a better description of the essence of humanity: the capacity to explore reality and look beyond appearances to uncover truths that are not immediately visible.

Remember: ALL science is essentially a fight against “the obvious.” For example (and you can find an infinite number of others), the obvious tells us that the Earth stands still while the sun revolves around it—but science tells us otherwise. And sometimes, science clashes with basic common sense: at some point, someone had to be crazy enough to suggest that people could live upside-down (in Australia…), and it’s no surprise he ended up on the stake.

So the main trait of intelligence—this very thing that sets us apart from the animal world and has allowed humanity to evolve—is this inner drive to question reality, to doubt, to seek creative solutions, to push for change, to ask whether what we see is really what is, to wonder if there might be a better way to do things, to ask “why,” “why,” “why!”

This impulse lives in all of us, to varying degrees, and it constantly looks for ways to express itself.

Which brings us to some key questions:

- What effect does this “intelligent” attitude—this questioning, this critical spirit, this urge to understand and change—have inside an organization?

- What if every musician in an orchestra were “intelligent”?

- What if every soldier started questioning orders from above? What if they asked “why”?

- What if every corporate employee began to challenge rules and search for “alternative” solutions?

- What if every citizen started questioning the law?

It doesn’t take much analysis to see that all of these would lead to chaos and anarchy and, very quickly, to the practical collapse of that organization. The inevitable conclusion is this: the more efficient an organization is, the LESS intelligent its members need to be. Any manifestation of intelligence causes inefficiency, complications, and wasted time.

Attention! The complexity of a function has nothing to do with intelligence—just like with a computer. If someone trains for years to master a position, but all they do is follow procedures set by someone else, then their behavior is NOT intelligent—no matter how long it took to learn those procedures.

And now we come to my inner turmoil: when I find myself in the role of a trainer (a role I’m increasingly reluctant to take on for exactly this reason), I face a dilemma. If I try to nurture intelligence in those who listen to me, I end up creating frustrated individuals who will only cause trouble within an organization.

But if I “train” them to perform as expected, the organization is thrilled—but I’ve essentially created robots: maybe highly efficient and well-prepared, but definitely NOT intelligent. And that bothers me.

I don’t have a neat conclusion for this article, but I can’t shake the feeling that every time I offer someone a “formula” or ready-made method, I’m dulling their intelligence. On the other hand, if I push them to think, to flex their creative muscles, I’m likely to cause even more trouble.

Once again, I want to express my concern about the direction our society is heading: we might all wake up as hyper-trained, high-tech robots who no longer need to use their intelligence, because everything has already been thought through and prepared. We’ll all apply the same standard recipes and methods, and maybe the world will run like clockwork.

And when we get home, we’ll listen to cheesy pop music, watch sports games, soap operas, and brain-dead TV shows—and who knows, maybe we’ll all be very happy.

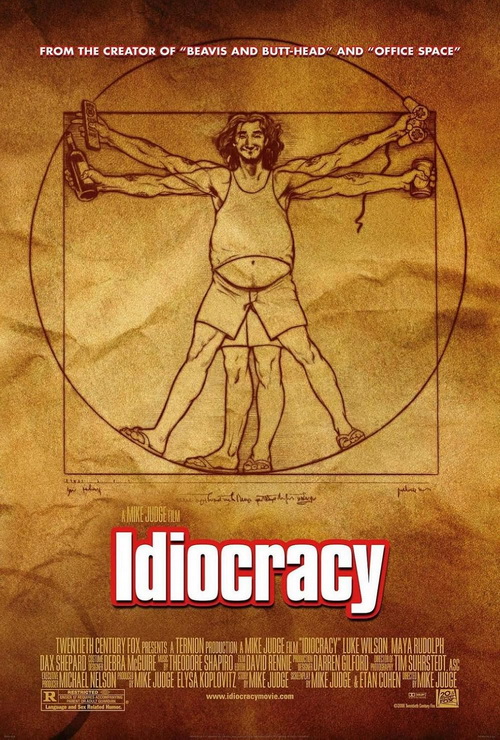

If you want a glimpse of what I think is coming, take a look here:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0387808

(It’s a science fiction film… but maybe it’s not all that fictional.)

Still, I can’t get one thought out of my mind—and I say this to all my fellow trainers: every day, we speak to dozens, maybe hundreds of people. And these people look at us, they listen, and they wait for a word, a piece of advice, a ready-made recipe. And it’s so easy to give them what they want—to energize them, feed them the usual buffet of positive thinking, motivational slogans, sales techniques, influence tactics, leadership tips. This makes them feel good and earns us their thanks and praise—at least for the moment.

But none of that helps them develop what makes them truly human: intelligence, creativity, character, the ability to read between the lines, to see beyond the obvious, to find solutions outside the box. And naturally, if we try to nurture this part of them, we’ll likely be met with hostility and resistance.

Each of us must find the answer we believe in.

Warm regards,